Our politicians and news analysts seem to have never taken a civics course. We see a population that increasingly finds conspiracy theories more plausible than their everyday common sense.

By John Simmons

Tis really astonishing that the same people, who have just emerged from a long and cruel war in defence of liberty, should now agree to fix an elective despotism upon themselves and their posterity.

Richard Henry Lee

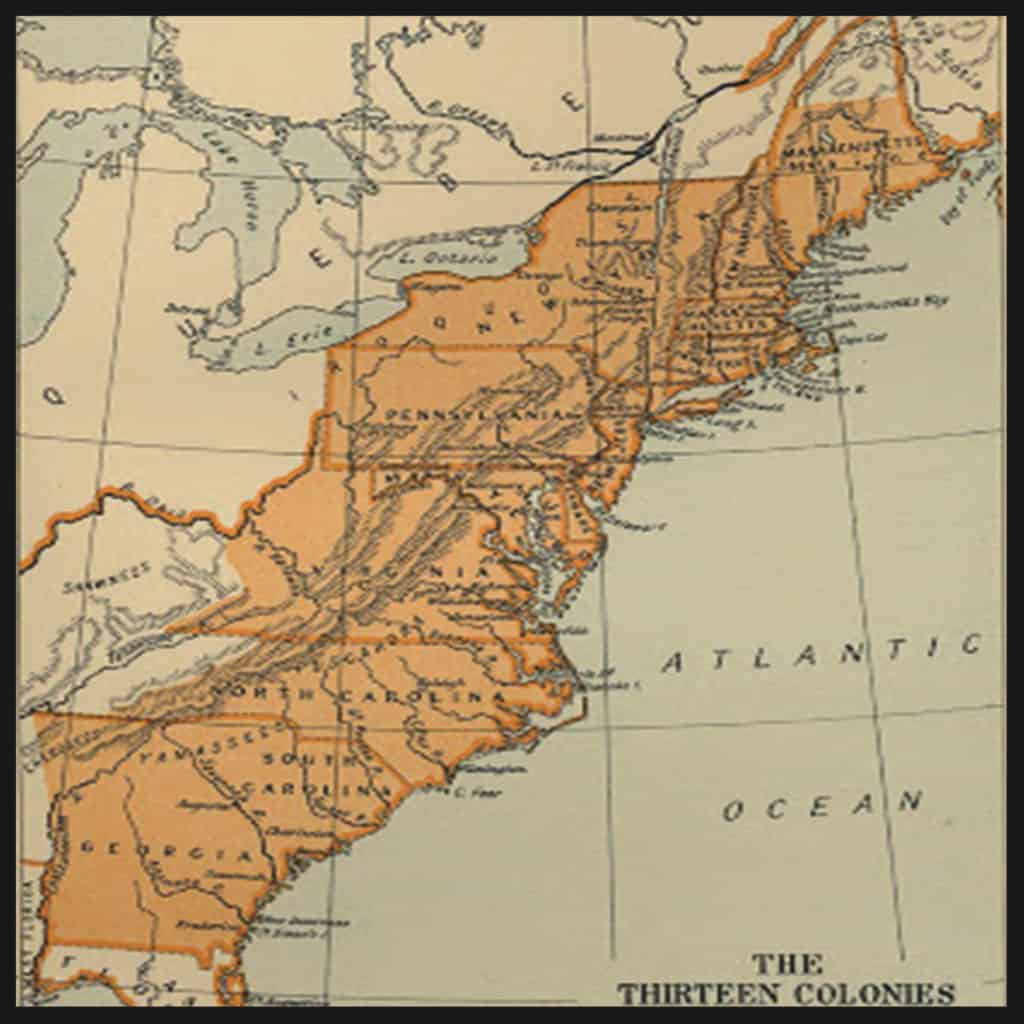

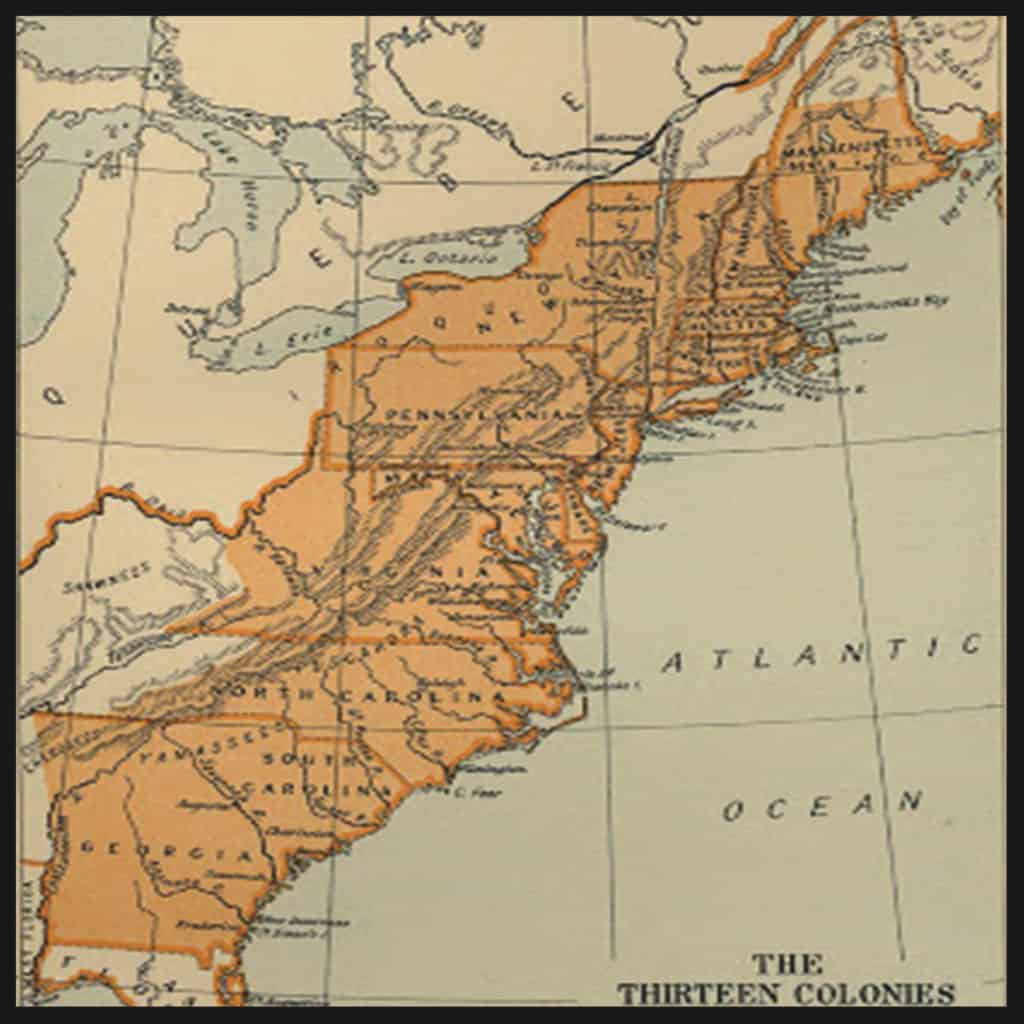

Prior to the American Civil War, those in the North looked across the 36”30’ line drawn by the Missouri Compromise and saw a lazy, ignorant and violent people who had a greater resemblance to the slave societies in the Caribbean or in South America than they did with the Republican vision of a more urban, more educated, more industrialized civilization. The South looked across at their northern neighbors and saw a meddlesome people, a greedy people that cared more about their money than about family values. They saw cities filled with garbage and crime and corruption. They saw the extinction of the yeoman farmer, and with this the end of the virtues necessary to the survival of a democratic republic.

The North’s version of Yankee Protestantism emphasized reform—their sermons preached temperance, public education, and the abolition of slavery. These notions fit in nicely with the Republican conception of Free Labor and of the upward mobility of ordinary citizens into the middle and upper classes. The Protestantism of the South was centered on individual salvation; an individual salvation that discounted any social analysis; that discounted class and race, education and reform.

The differences in the economic systems of the two sections is well documented. The North had better infrastructure, greater industrial output; greater population growth. The economy of the South was dominated by agriculture, with nearly all its wealth tied up in land and slaves. Its cash crops of cotton and tobacco, rice and indigo gave the U.S. the advantage in its balance of trade. Although every White person stood above every Black person according to the prevailing laws and practices, only 3% of the population owned 12 or more slaves. Nevertheless, every White person believed they benefited in some small way from the peculiar institution; and every White person was very defensive about the opinions of Northerners regarding their way of life.

Ultimately it was the country’s expansion into new territories that threatened the balance of Slave and Free states. This led to political intervention, which set the stage for the Civil War. Here Clausewitz famous equation of politics and war, of war being one of the instruments of policy, is instructive. War became possible when only politics could adjudicate the civil crisis, and war became necessary because a Free America and a Slave America were no longer compatible, and only one could remain.

It is natural to look back at our history and try to draw lessons from it. We try to see the causal relationships; we try to trace the inevitability of civil war. Clearly the North and South lived different lives; clearly they were keenly aware of their differences and their policies and compromises reflected a sober acceptance of them. We look at our situation now and wonder how close we are to Civil War or to some great moment of social upheaval. We think in terms of Red and Blue states, and we wonder, is it a stretch to say that Red and Blue states form sections with completely different economies or ways of life? Stretch or not, our level of emotion, our level of irrationality and extreme rhetoric, is disturbing and should give us pause.

2.

What is it that unifies us as Americans; what is it that allows us to work together towards a common purpose? Four score and seven years before Gettysburg there was a level of unity in America adequate enough to sustain us through our break with England. After the war, the Articles of Confederation were adopted at the Second Continental Congress, and when these proved ineffectual in promoting the growth of the new Republic, Madison and the Federalists were able to negotiate a compromise in Philadelphia and create (and then go on to ratify) our Constitution. These achievements are now rightly regarded as a miracle. Consider Richard Henry Lee’s assessment of the situation: “’Tis really astonishing that the same people, who have just emerged from a long and cruel war in defence of liberty, should now agree to fix an elective despotism upon themselves and their posterity.” This astonishing level of agreement, that allowed us to ratify the Constitution and sustain the subsequent rule of law as each branch of government grew stronger and exerted its full political influence, demonstrates a powerful underlying willingness by the Founding Fathers and the subsequent generations to compromise.

This willingness to compromise appears more astonishing looking at it from the present day, at which time legislators cannot even manage to compromise enough to agree on simple facts about an election or to pass a stimulus check to its people in the midst of a pandemic. When we look back on the sectional differences of early America, we should marvel at the fact that they did not have a constitution to help them overcome their differences. Rather, they wrote and ratified a constitution despite their differences. In 1788, the people of this country chose to unite under a stronger central authority quite against their better instincts and judgments because, although they certainly exhibited a healthy lack of trust towards any centralized authority, they did not exhibit a lack of trust in each other.

Right now we seem to cling to the Constitution as the one thing that will pull us through these divisive times. And yet, we had no Constitution when we defeated the British, and we had no Constitution to speak of when we wrote and then ratified The Constitution itself. Therefore it must have been something else that saw us through the Times that try Men’s souls. And whatever it was that we leaned on to get us through this period did not manage to sustain us, despite having a Constitution for nearly four score and seven years, once Lincoln was inaugurated in 1860 and shots were fired at Fort Sumter. It seems fair to conclude that the unity that sustains us as the United States of America is something other than, at least something more than, The Constitution of the United States.

3.

We are trying to find a way to think clearly about unity and change in America.

Change is constant; change is absolute. If there is anything to be learned from history, this would be it. But we would like to control change so it does not rip us apart. We would like to change together; we would like to remain together as a nation. It is fair to describe the function or role of the Constitution as the rules for the activity of change. If change were a sport then the Constitution would be the rules of the game. What these rules guard against is dictatorship; tyranny; despotism; factionalism; etc. In the pursuit of change, the Constitution makes sure that one group or person cannot take over the process, and in effect stop change from happening. But as we have argued in the second section, the Constitution is not what keeps us together; it is not what underlies our unity. The Constitution is not any kind of answer, not any kind of outcome; not any kind of blueprint for how to live our lives. It is not any kind of unity in itself. The changes we ultimately decide upon do not flow out of the Constitution; we cannot derive them from the Constitution. Therefore, doctrines that raise the Constitution to the level of a Unifying Value are absurd. The Constitution, like the rules of any game, is not the reason we play the game, and it does not represent the playing of the game itself.

It has often been noted that the Declaration of Independence is the document that specifies the essence of American values and the essence of our unity. We set the Declaration beside the Constitution and together they lead us forward. However, it is not the case that the Declaration of Independence accurately describe the underlying values that unite us. For one thing, the Declaration deals in rights as opposed to values. We need to understand the difference between the two terms. Jefferson invokes the term rights, as in “unalienable rights,” because he is trying to motivate individuals; he is trying to define each individual’s stake in the rebellion against British Rule. He is expressing Locke’s idea of a Social Contract, used to defend, for example, the Glorious Revolution. However, it is not accurate to say that we are united by individual rights. Rights do not exist outside of some well-defined social structure that bestows them on each of its participants. In this case, these rights exist because of a theoretical contract Americans have as citizens of England. And we did have rights as British subjects. For example, we had the right to representation in Parliament if we were taxed by the crown.

In order for Jefferson to create a sense of entitlement to rights outside of any country or political structure he had to describe our rights as self-evident and unalienable and endowed by our Creator. This gave us the right to revolt, to dissolve the political bands that connect us. And although the right to revolt might accurately describe the unifying force that carried us into the Revolutionary War, it is not the unifying value of a country trying to avoid civil war.

What is given by our Creator and does reside outside of any country or political structure are Values. But Values are notoriously difficult to define. We discover them at the same time we define them, by making decisions. We are left to sort out these values, and to negotiate and prioritize them in each situation. But these negotiations, these decisions are not random; we are able to evaluate them and learn from them. So there must be something that we hold up against our decisions before or after we make them, and therefore there must be something we can say about values to help guide us.

The most important point to make about values is that they are a relationship among people, among individuals; they are the glue between individuals. There is no such thing as an individual value, and insofar as we value liberty, for example, an individual’s right to liberty only makes sense because everyone in the community has this same right. The notion that America is the sum of all the individuals that each possess their own inalienable liberty is absurd. Madison surely understood this when he saw no value in adding the Bill of Rights. The government he helped design was not going to bother anyone as they pursued their happiness. The pursuit of happiness is closer to naming a value that binds us together, but it is not specific enough to unite a nation. If you told your children that they had the right to pursue happiness, they still would not know what they were supposed to be doing.

Consider this analogy when comparing American Values with the individual rights of American citizens. A person playing basketball has the right to shoot a jump shot without being fouled, but the game of basketball is not the sum of all the players’ individual rights. The game of basketball could not be learned, could not be played, according to the sum of all the players’ individual rights. Rights describe a situation in the midst of playing in which our pursuit of some value is undermined, and a remedy needs to be applied. A basketball player is fouled, and the referees let her shoot free throws. At that moment we recognize that individual player, but her right is not something she possesses as an individual; it is something she possesses as a participant in the game. The game has rules that apply to everyone equally, and the game has the values we associate with playing a sport that are expressed by everyone in their play. The remedy is supposed to put the game back on track, so that the value of competition and of winning can then be pursued. But we are not motivated or united by our right not to be fouled. We cannot derive a zone defense, an out of bounds play, or even a winning strategy in terms of the rights of the players.

Similarly, we are not united to pursue happiness by the sum of our individual rights. And when we fight for our rights, either in making laws or interpreting those laws, it would be difficult to make a judgment if we did not know the value of it; if we did not know the purpose and the pursuit behind those rights. Thus, when we consider what unifies Americans, it is not individual rights, it is not The Constitution, and it is not the Declaration of Independence.

4.

Along with a misunderstanding of rights and values we have also developed a misunderstanding of the meaning of the terms conservative and liberal. Within the framework being described here, the role of Conservatism is the preservation of Unity. Conservatism should not be associated with a lack of social change, or with impeding social change. We would not call someone a basketball Conservative if they advocated that the score in the game should never change. Conservatism certainly should not be associated with sowing disunity for the purposes of advancing the interest of some group or faction. Conservatism in basketball cannot be paying the referees to make bad calls in favor of the team that is currently winning, or injuring the other team’s star players just to secure a victory. And finally, Conservatism should not be associated with preserving one expression of values over another. Conservatism cannot be used to decide that a Rembrandt is art, but a Renoir is not. Conservatism cannot decide that a woman is less valuable than a man. Conservatism cannot decide that post-up play is more important than three-point shooting in basketball—winning and losing will decide that question. Conservatism simply assures that the structure of unity is intact as we pursue our values, so that the rules and definitions and playing field are not shifting under our feet.

Social change is the natural outcome of individuals and groups pursuing their values. However, sometimes the values expressed in one activity come into conflict with the values expressed in another activity. Here it becomes clear that each activity is unified based upon some set of values and each activity bestows rights to the participants by way of its rules or traditions, and that in between these activities, in that space where we might have to make a ruling about one activity and its values over another activity and its values, there is a vacuum of power. It is in this vacuum of power that Politics rushes in.

Just as Conservatism is not a conservation of outcomes but an agreed-upon process that maintains unity through all outcomes and all changes, neither can change itself or some particular change, some particular outcome, be a source of unity. This is the error we associate with Liberalism. In the age of single-issue politics, of interest groups and lobbyists, we see groups unified in the interest of a particular outcome, and they have taken advantage of a political system that is not designed to unify or adjudicate the interests of competing groups. The political system is not a market economy, for example. Neither is the government a corporation, making and carrying out specific plans to achieve specific outcomes. And yet we expect the government to fix all of our problems, and to behave as efficiently as a corporation. This liberal tactic of forcing change by uniting people and resources around a single outcome is stunting our natural growth; it is undermining the progression of change, and creating a fragile unity that can be swept away at any time. It is a cynical approach to our problems.

In a sense, politics has become a sport without rules. It is as if we are following Machiavelli’s advice for The Prince rather than his advice for Republics in his Discourses on Livy. If the underlying values that unite us are lost, then the rights and the rules of the game in The Constitution do not have a clear meaning. In this case, how can they be applied? If there are no agreed-upon values in our politics, if the ends justify the means in politics, then there can be no real rules or rights, there can be no Unity, there can be no Conservatism, and there can be no meaningful Social Change.

5.

When we consider how unity and change are two sides of the same coin, we see that conservatives and liberals are two sides of the same coin, each with a role to play. Currently, however, Conservatives are inadvertently undermining unity, undermining the ground that holds America together through its changes. Currently Liberals are pegging unity to certain changes or certain outcomes. The misguided perceptions of the last century about a market of political interests and about efficiency in government has led us to the current misconceptions. We conceive of our government in terms of analogies rather than in terms of knowledge. These analogies are meant to describe our behavior, perhaps apologize for it, but they are not meant as an analysis of how to put things back on the correct track.

Our politicians and news analysts seem to have never taken a civics course. We see a population that increasingly finds conspiracy theories more plausible than their everyday common sense. This ignorance about the role and the operation of government is made more complex when our ignorance about the very values that unite us are ripping apart any rational conception of the role of government and its operations. Blaming any one social practice or group of people is not going to get to the root of this problem. We are all to blame. What we need to ask ourselves is this: what kind of a country do we want to be? What are our unifying values; what is our unifying vision of America? We also have to understand the role of our government in this vision: what it is designed to do and what it is not designed to do. And we need our citizens to be educated about these things, because that is the only way a democracy can function.

Redefining Power

Redefining Power