Sir Paul Collier is the champion of the bottom billion, using pragmatism and evidence-based reasoning to take Economics to neighborhoods that it usually avoids.

By Robert Simmons

Modern capitalism has the potential to lift us all to unprecedented prosperity, but it is morally bankrupt and on track for tragedy. Human beings need a sense of purpose, and capitalism is not providing it. Yet it could.

Sir Paul Collier

Ever the pragmatist, Sir Paul Collier, Professor of Economics and Public Policy at the University of Oxford, would rather have issues be resolved, and to that end has been willing to expand the boundaries of economics to include real people, and introduce evidence-based analysis in place of the usual economic dogma, which has only served to reinforce the status quo. As someone who is one generation removed from the curses of immigration and poverty, Sir Paul has spent a lifetime trying to solve the dilemmas of low-income countries, and understand the part of economics that fails all of us.

Currently, 97,000 students are enrolled in his EdX course “From Poverty to Prosperity”, which is a history lesson on how humans societies were formed – where they have gone right, and where they have gone wrong – with his own special take on how conditions could be improved. He has spent time working with the World Bank, and through his research on their behalf, helped foster policy change in Africa – an accomplishment for which he was knighted in 2014. Somewhere in between all of this, he has found time to write nine books; we will highlight three of them here.

The Bottom Billion

Seventy-three percent of people in the societies of the bottom billion have recently been through a civil war or are still in one…the American, Russian, and British civil wars were…over fairly quickly and not repeated. For low-income countries, however, the chances of war becoming a trap are much higher.

Sir Paul Collier

The Bottom Billion establishes Sir Paul’s penchant for evidence-based research, to uproot the underlying and most salient commonalities, before trying to propose any economic solutions to them.

He found three main drivers of conflict:

- Poverty (low income)

- Negative growth (which could arise from the anticipation of civil war, that makes investors flee, thus initiating this phenomenon)

- Non-governmental control of a country’s primary natural resources

“So what characteristics..make people more likely to engage in political violence? The three big ones were being young, being uneducated, and being without dependents.” – Sir Paul Collier

Social justice is not the core reason for violent protest; it is greed. No violence occurs until there is a valuable resource in the picture. He found if there was only one oil well in a region, extortion was highest; when several oil wells existed, oil companies had enough financial ‘incentive’ to pay the locals something in order to keep the peace.

In one of many examples offered in the book, Rebel leader Laurent Kabila was marching across Zaire with his troops, to seize the state. He turned to a journalist traveling with them and quipped that in Zaire, rebellion was easy. “All you need is $10,000 and a satellite phone.” The $10,000 was to buy a small army of poor citizens, and a phone was needed strike deals with resource extraction companies, who do not care who runs the resources, as long as they have stable enough access to them. International companies will pay rebels lots of money in the hope they will rise up, and get control of these resources. Kabila reportedly struck $500 million in resource deals with investors before even reaching the capitol in Kinshasa (to “liberate” it).

Rebel leader Foday Sankoh led an army of teenage drug addicts in his bid to control the diamonds of Sierra Leone. George Speight cried “Fiji for the Fijians”, in an attempt to wrestle away a lucrative mahogany contract for a private U.S. corporation (of which George was a consultant). Because there is often no centralized government control of a country’s resources, and capitalists, who like it that way, promote instability in order to gain direct access to these resources, a form of colonialism still continues to exist today.

“Ninety-five percent of global production…of hard drugs is from conflict countries.” Again, because of instability and conflict, illegal operations are more capable of running their businesses undisturbed.

Other factors work against the countries of the bottom billion. If they are 1) landlocked (no port for the exchange of goods) 2) resource-scarce, and 3) surrounded by “bad” neighbors (also in a period of conflict or instability themselves), there is little hope for salvation.

Countries need manufacturing to develop, but if a country is landlocked, it must transport its manufactured goods through its neighbor’s territory, in order to reach a shipping port. Switzerland has nice neighbors with stable infrastructure (Italy and Germany), while Uganda has only Kenyan Infrastructure. Because neighbors matter, conversely, when a country has troubles, these troubles invariably spill over and affect surrounding regions. The takeaway here is that ultimately, all our fates are tied together, and the pragmatic thing to do is solve issues of stability and peace first, by seeing people as an integral part of the economic equation.

The trap of resources is a game theory prisoner’s dilemma – on one side, the rich resourceless country simply wants the goods, and is willing to look the other way in order to get them; on the other side sits the resource rich country with no stability. Interestingly, the payment for these resources ends up more expensive than what it would cost to simply give some form of aid to the country.

Landlocked regions need to have air transport, good telecommunications (for e-commerce), trade across borders to improve economic development in the entire region, secure coastal access, and an investor-friendly setup that is stable and transparent.

Once conflicts are tenuously resolved, new governments tend to invest in military protection (to consolidate their victory), rather than economic development, which Sir Paul asserts would be money better spent, in order to keep the peace (reversing “negative growth” provides hope, which leads people toward trust, which facilitates cooperation). Mozambique, for example, chose to invest in development instead of a military, and so far peace there has endured.

Exodus – How Migration is Changing Our World

Migration has been politicized before it has been analyzed.

Sir Paul Collier

In Exodus, Sir Paul tries to better understand the emigration of people from their home country, and how that affects those left behind, as well as those indigenous populations who are the recipients of this immigration.

“Economists have a glib little ethical toolkit called utilitarianism…But for a question such as the ethics of migration it is woefully inadequate.” – Sir Paul Collier

Sir Paul admits that the economics of greed is not fit to answer the bigger questions and concerns that this kind of economics creates. It has a blindspot: it doesn’t see people very clearly. Sir Paul seems bent on rectifying this, utilizing the disciplines of philosophy, social psychology, ethics, and more, in the service of understanding the whole person and what motivates us beyond self-interest.

The migration of poor people to rich countries can be seen as “imperialism in reverse” (or ‘what goes around comes around’); when the wealth of one area has been drained by outside forces, those left behind are wont to migrate in the direction of this extracted wealth. From an economic perspective, maintaining planetary equilibrium is healthy; thus the economic tendency is to encourage open borders. In this way, the rich must either learn to keep their hands off of other people’s stuff, or be prepared to deal with the ensuing ramifications.

Unfortunately, those who are tasked to make policy are “caught in the crossfire between the value-laden concerns of voters” (who favor a closed-door policy), and the open door models of economics. According to Sir Paul, “our ethics determines the reasoning and evidence that we are prepared to accept.” In other words, we form opinions prior to knowledge, then only accept knowledge that validates our pre-formed opinions. In this way, no thinking actually takes place – thinking that could lead to meaningful solutions. To ensure the continued lack of thinking, controversial subjects often get filed under the heading of “taboo”.

“Very recently, economists have gained a better understanding of the structure of taboos. Their purpose is to protect a sense of identity by shielding people from evidence that might challenge it. Taboos save you from the need to cover your ears by constraining what is said.” – Sir Paul Collier

Through this, Sir Paul is able to conclude that our values are more important than reasoning or evidence, as the fast thinking “snap judgements” we make are not rooted in any type of “effortful thinking”.

“I can think of no other area of public policy where differences are so pronounced [as in immigration]. Does this diversity of policy reflect sophisticated responses to differences in circumstances? I doubt it. Rather, I suspect that the vagaries of making policy on migration reflect a toxic context of high emotion and little knowledge.” – Sir Paul Collier

It is a flimsy tightrope Democracies must walk, as the Nationalism borne out of the protection of one group’s identity often manifests itself into a ‘tyranny of the majority’. In Switzerland, where the government gives its people the right, through referendums, to change local policy, the people used it to forbid the building of mosques in their communities; a decision that the government had to reverse for its “embarrassingly” ignorant affront to personal liberty.

“Most migrants from poor countries are racially distinct from the indigenous populations of rich host countries, and so opposition to immigration skates precariously close to racism.” Sir Paul Collier

The general pattern of migration is to leave one’s people behind, only to enter a host country and immediately seek out one’s ‘people’ living there. This raises the anxiety of the indigenous population, as the newcomers are socially walled off in “diasporas”, such that overall community trust or shared identity has no chance to form. This only foments fear and speculation, as immigrants may be seen to take away jobs, while eroding the indigenous population’s values or belief systems simply by introducing their own. It sometimes takes decades for new arrivals to be absorbed into the general population (often through the next generation of kids, who are now perceived as “natives”, and more tempered by the process of assimilation). Only then can trust and shared identities begin to form again.

For now, it seems that host countries can only handle so much immigration; after a period of “no restriction”, there seems to be an “anxious” phase, followed by a “panic” phase, that eventually turns “ugly”, forcing immigration policy to freeze until a balance can be attained, and trust can be restored among communities. Sir Paul points out that some of the most underpopulated countries: Canada, Australia, Russia, and Israel, are the most strict in their immigration policies. Australia is seen as an immigrant’s dream destination, but immigrants have very little chance of legal entry as this time.

“…it is no longer necessary to discard national identity in order to guard against the evils of nationalism.” Although Nationalism has taken many countries down the road to war, Sir Paul believes that the formula for cooperation is a function of trust, and trust is dependent on people having a shared identity. Again, the tightrope we must walk is to invoke something that binds us together beyond ethnicity or religion or politics, that can unify us around some shared identity; otherwise, no solutions will be forthcoming.

The Future of Capitalism

A moral capitalism that supports esteem and belonging, alongside prosperity, is not an oxymoron. Understandably, however, many people think that it is; they judge capitalism to be fatally tainted by relying on the single drive of greed.

Sir Paul Collier

In a continued attempt to bring us together around a shared identity, Sir Paul explores the current rift between us, explains the origins of our varied belief systems, and identifies the values common to all people, regardless of geography.

“The glib supporters of capitalism who argue that the end justifies the means invoke Adam Smith’s famous proposition in The Wealth of Nations that the pursuit of self-interest leads to the common good. ‘Greed is good’ became the intellectual underpinning for the zeal of the Reagan–Thatcher revolution.”

Sir Paul reminds us that Adam Smith wrote another book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), that shows Smith did not believe man was only the sum of his greed, but had a capacity for empathy and judgement as well – sentiments that led to morality. Paul cites Nobel Laureate Vernon Smith for seeing the common theme in both of Adam Smith’s books: the mutual benefit derived when things are

exchanged between people, whether in the marketplace, or in the service of doing good for each other. Sir Paul calls these two exchanges Wants and Oughts; there are things people ‘want to do’ and things people ‘ought to do’. These moral obligations are what make us more than the selfish, lazy, greedy Economic Man depicted in modern Consumerism.

Sir Paul is on a mission to evolve economics past this “psychopathic” view of man, which has short-changed all of us in pursuit of “maximizing utility”. He seems to borrow from Abraham Maslow, in identifying “esteem” and “belonging” as the underpinning of our moral values. These two social needs drive the six values that social psychologist Jonathan Haidt believes we all share,: care, liberty, loyalty, sanctity, fairness, and hierarchy.

“Care and liberty may be evolutionarily primitive. Loyalty and sanctity may have evolved as norms…and internalized…as values because they were rewarded with belonging. Similarly, norms of fairness and hierarchy may have evolved to keep order in the group, being rewarded with esteem.” – Sir Paul Collier

Sir Paul prefers people try to frame “rights” as ‘reciprocal obligations’ instead of as entitlements. For “one person to have a right, someone else must have an obligation” to uphold that right. Meanwhile, we have conveniently decided to slough off all rights / obligations onto government, which, apart from a passing cordiality, apparently means we no longer have any real obligation toward each other. Unfortunately, reciprocal obligations, when disregarded, tend to erode. They must be practiced, in order to maintain civic virtue, a crucial component of Democracy, as preached by the philosophy of Michael Sandel.

The story so far: the part of the population that is skilled and educated has tended to sheer off from ‘Nationality’ as its core identity, leaving the less fortunate clinging to its diminished status. In turn, this has resulted in the weakening of shared identity across society.

Sir Paul Collier

In the times of World War, an outside force has given America a shared identity, but in times of peace, when Nationalism is discarded for individual achievement, those who remain behind in this Nationalist mindset can feel somewhat abandoned. According to Sir Paul, if we can bring a sense of reciprocal obligations back into the three main groups that dominate our lives: Families, Firms, and Societies (Communities), it may be enough to push Capitalism in a more ethical direction. Unfortunately, our genetic survival toolkit is only designed to react to the threat of outside danger; if humans are to bond in times of peace, we must learn to form this bond from the inside, which is something that does not come naturally to us. Enter Education.

“School is not really a preparation for life: it is a preparation for training. At its best, it will have equipped some people with cognitive abilities that can be honed into skills…But the non-cognitive abilities will not have received the same attention.” If we are to have a shared identity that reaches beyond nations and languages, ethnicities and religions, it must be learned, and then practiced, until it becomes part of the many routines that make up our modern lives.

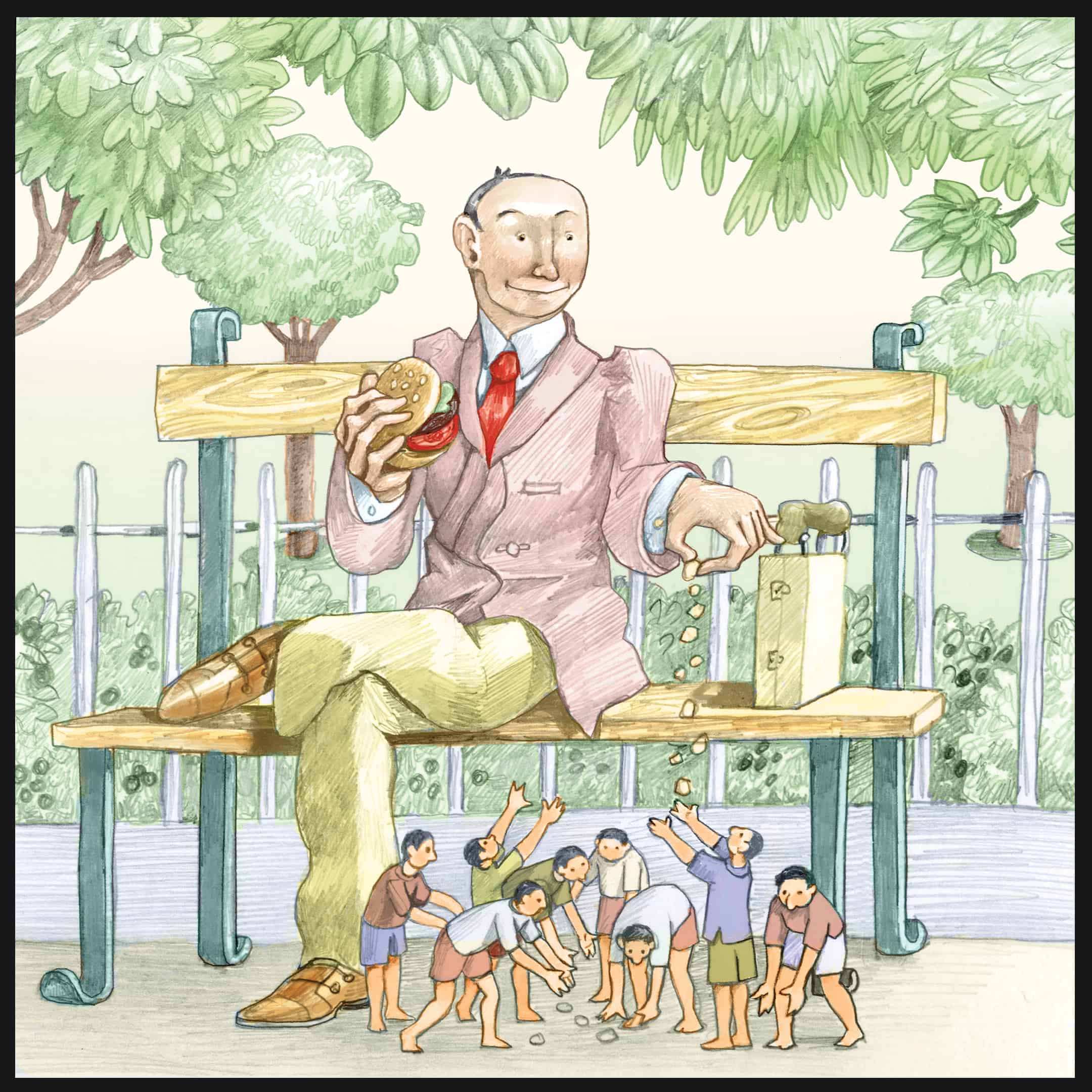

In building this new ethical world, we must also come together around a shared sense of economic value. In his discussion of Economic Rent, Sir Paul explains that when people flock to a city, economies of scale increase; costs are made lower and productivity rises, due to the concentration of workers. Those ‘landlords’ who happen to own the property where the city is built, are allowed to drive up rent for housing from the very people who are creating this wealth; these are known as “gains from agglomeration”. Henry George, a 19th century political economist, questioned whether landlords should get all the wealth created by this working class of people.

“The gains from agglomeration are generated by the interactions between masses of people, and so they are a collective achievement that benefits every one. This is something that economists refer to as a public good. So, what part have the landowners played in this process? For all that they have done, they might as well have been lying on a beach..they have received the income because they owned land where people happened to cluster. In the confusing vocabulary of economics, it is classified as an “economic rent… Their gains are purely from entitlement. This collides with the collective claim of all the workers in the city to those gains, which is based on desert.” – Sir Paul Collier

We Hear You, Professor Collier

States that link ethical purpose to good ideas have achieved miracles.

Sir Paul Collier

The Third Option wants Sir Paul to know that we are doing our part. We fully believe in reciprocal obligations, which can be learned through education, then spread to community, which would solidify the nation around a shared identity, and inform the planet of its viability. With the tools of emotional intelligence and civic virtue, this shared identity of values can be forged.

In the area of immigration, The Third Option proposes the building of Global Schools, at first along our U.S. border, and later, branching out into every country that would accept our presence. These would be places of shelter, learning, and healthcare for arriving immigrants, and would offer each one a two-year associate degree-level education that includes language, self governance, and ethics, as well as essential needs ‘training’ in specific areas like healthcare, housing, agriculture, computer science, energy, and more.

After this two-year training program, Immigrants would be asked to perform a year-long ‘mission’ to a different Global School, either in their native country or in one of their own choosing. During this ‘mission’, they would help spread these shared values, along with the technical knowledge to create the infrastructure necessary for low-income countries to achieve sustainable self governance (materials needed to realize this infrastructure would also be made available – ‘reciprocal’ arrangements would be made, that do not necessarily have to be financial in nature).

At this point immigrants would become U.S. citizens, and encouraged to join a specified community, to help foster the spread of diversity; or they could return to their country of origin, and help improve the social model there, so that eventually, no one need choose to flee their native country for reasons political, societal, or economical.

“As an economist, I have learned that decentralized, market-based competition – the vital core of capitalism – is the only way to deliver prosperity.” – Sir Paul Collier

We believe that what drives Belongingness is actually belonging. What drives Fairness is actually being fair. We also believe that when Certainty is compromised, anxiety forms, which erodes trust, that severs reciprocal obligations, and with it, any chance at a shared identity.

Sir Paul would be the first to admit that he, too, is limited by his belief system, which for him, centers around the economics of Capitalism, that will forever be at odds with Belonging, Fairness, Certainty and Sustainability, because it is still infused with the “greed” of ‘Thugs’ (Sir Paul’s word for Oppressors). Oppression cannot be severed from Capitalism until we, the descendants of Thugs, admit to this tragic flaw in our personalities; only then will we embrace this discipline of ethics, which will require a lifetime of “effortful thinking” to maintain. Until we know our true selves, we have no hope of looking at the evidence truthfully, and drawing honest conclusions, which are the only kind of conclusions that will lead to correct (and thus viable) decisions.

Sir Paul has certainly traveled as far as Capitalism could possibly take anyone. Seeing how corporations (like those clustered around Stanford University, forming ‘Silicon Valley’) benefit from economies of scale, Sir Paul reasoned that perhaps a Bank, expressly designed for a community, could get capital flowing into less desirable areas, and create economies of scale anywhere on the planet. He even reasoned that perhaps “government” could help coordinate this. His research has clearly shown him that without strong centralized government, countries cannot prosper, but still falls short of proposing a National Public Bank, opting instead for some Developmental Bank, along the lines of his former employer, the World Bank, who many see as having been a curse to the Bottom Billion.

Socialism. Fascism. Communism. Governments don’t fail because of ideology, they fail because oppressive leaders are allowed into the driver’s seat. Capitalism has not proven to keep oppressors out; even Democracy has trouble doing it. Government needs to be stripped down to a single tool so large, that it takes the entire population in order to lift it up and wield it. Our Income taxes, deposited as ‘seed money’ into a National Bank, then dispersed equally among community banks, could infuse capital into local businesses, meanwhile rebuilding the larger infrastructure platforms of Education, Healthcare, Energy, Transportation, Communication, Water / Sewer, and Agriculture, to allow the free market to flow, entrepreneurs to shine, and monopolies to be rendered impotent. The Bank implies that the owner of a nation’s currency is, in fact, the people who have

consented to being governed, and whatever the Bank builds, the people own; and whatever the Bank accrues in profits, the people also own. Finally, our fates would be tied together, through an economics built on a raised floor, but with no ceiling. Economic Democracy is the best partner to Democracy. Capitalism is an excellent pairing for Authoritarians and Autocrats. Let it go the way of those types. Godspeed.

Republicans. Democrats. Drug dealers. Gang members. The problem with belonging in a group is that, unless you stick with the belief system being crammed down your throat, you could be shunned. Ostracized. Shamed. Economists are a gang, also. It would likely be professional suicide to admit that Capitalism is just another (albeit better disguised) form of Oppression. If you did, however, decide to take that final leap, Sir Paul, we at the Third Option would be here to catch you. We’ve been down at the bottom, waiting, for quite a while.

Should a Handful of People own the Rights to Every one Else’s Rights?

Should a Handful of People own the Rights to Every one Else’s Rights?